By Sara Fattori, Observa Science in Society

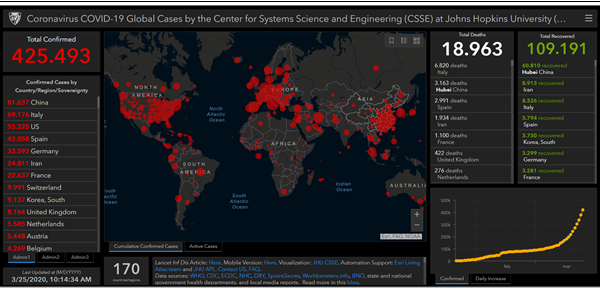

Figure 1: COVID-19 outbreak 03-25-2020; Center for Systems Science and Engineering (CSSE) at Johns Hopkins University.

After China, South Korea, Iran and Italy many countries around the world have been heavily hit by the Covid-19 pandemic, something initially perceived as a “far away” problem now presents itself as a public health crisis and national emergency for many countries in the European Union, as well as for the United States. This virus, that first appeared like many others, had rapidly turned into an aggressive pandemic affecting a large amount of the population.

To staunch the number of cases, many governments had to impose severe restrictions on its citizens’ movements and enforce social distancing and self-isolation. Non-essential businesses have been shut down, as well as schools and universities; access to public spaces have also been limited or forbidden in most places. Restrictions on daily activities forced people to move online to study and to work. With increased reliance on digital technology, the incentives for malicious actors to launch attacks, such as phishing, has also increased. In addition to such cyber security topics, authorities have been challenged in terms of crisis and information management, as disinformation started to spread after weeks of overflowing information on the web, social media is populated with different kinds of misinformation about SARS-CoV-2.

On February 15th 2020, during his speech at the Munich Security Conference, WHO3 Director General – Dr Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus – pointed out that “[…] we’re not just fighting an epidemic; we’re fighting an infodemic. […] Fake news spreads faster and more easily than this virus, and is just as dangerous. That’s why we’re also working with search and media companies like Facebook, Google, Pinterest, Tencent, Twitter, TikTok, YouTube and others to counter the spread of rumours and misinformation. […] We’re concerned about the levels of rumours and misinformation that are hampering the response.”

Figure 2: Homepage of the WHO. All the information and latest news about COVID-19.

Despite the effort made by digital platforms and public authorities to give official sources priority visibility online, there is still confusion amongst the public on whom and which online sources to trust. This confusion lead people to trust the wrong sources, believe in false claims and engage in risky behaviour. Fake news can be as dangerous as the virus itself. Fabricated news, like rumours, often spread faster than accurate news due to fake news’ tendency to tapping into people’s emotions and engaging in conspiracy theories. Difficulties in explaining complex scientific topics in clear and concise terms also make consuming and engaging with accurate information more difficult.

One example of fabricated information spreading quickly is through online chatting APPs. As fast as the COVID-19 contagion, false and unverified information ran across messaging APPs and group chats, that even the Irish Prime Minister 1 warned his citizens about the danger of sharing unverified information through WhatsApp in a tweet.

Figure 3: Tweet from official account of Leo Varadkar – Irish Prime Minister.

Media sources spreading false information, further complicated people’s access to accurate information. One example is Alt News Media stating that the reason Northern Italy was hard hit by the contagion was because of the Chinese workers from infected regions such as Wuhan traveling to Italy for work. This below tweet came from David Vance’s Twitter account, who has 155.4K followers.

Figure 4: Twitter – Example of fake news about COVID-19 outbreak in Northern Italy

The EUvsDisinfo database has been accumulating coronavirus-related disinformation cases for more than two months, and it offers interesting insights. 39 of the collected disinformation cases claimed that the US created the coronavirus, and several other cases implied that the EU is failing to cope with the crisis and is disintegrating as a result.

This widespread misinformation consumption begs the questions how can people’s media literacy be improved? What tools are needed to help people be more critical in order to recognize and avoid fake news?

One possible solution is scientists and public institutions partnering with social media4-5-6 platforms to better communicate reliable information, data and statistics, policy decisions, and offer advice on dos and don’ts. The emergency scenario changes quickly and social media seems the most effective channel to reach out to the masses and update the population on the evolution of the pandemic. Below are some examples of outreach communication campaigns conducted via social media.

Figure 5: Twitter Italy – COVID-19 latest news and information from official and reliable sources.

Figure 6: Facebook Italy – Official information page

Figure 7: Infographics as a way to visualise and communicate data effectively

Data speaks volumes but they need to be communicated in an effective way to be comprehensible.

According to a recent survey conducted in Italy by OBSERVA – Science in Society (March 2020), 52% of participants said they obtain information from TV News channels, while 20.5% prefer official websites such as the Ministry of Health and the Civil Protection Service webpage or from websites of regional governments. Only a small percentage admit to consuming information coming from social media.

Public understanding of science is important because it influences attitudes and behaviours. Perceiving a public policy to be legitimate increases one’s willingness to comply with it. Moreover, some groups are more vulnerable than others to misinformation. According to an Observa study of Italian’s responses and behaviours, they found 48% fall into the “trustful quarantine” type: they are oriented towards a series of personal precautions, followed the indications of the institutions, and judged positively the way institutions are managing the crisis. This type of people is more common in the female population, among the over-sixties, with a low educational qualification, and with low level of scientific literacy. 30% fall into the “fatalist social media” type: according to them, the pandemic is out of control, people are powerless, and institutions are managing the crisis very badly. The favourite sources of information for this group is social media and relatives or acquaintances, whom they rely for practical information on how to deal with the contagion. This type is more common amongst males who are 30-44 years old. Finally, 22% fall into the “misinformed underestimation”: this group of people are not informed. They do not know how to judge the work of the institutions and tend to strongly underestimate the risk of the situation. It is worrying to note that this attitude is particularly widespread among young people.

The perception of the risks brought on by COVID-19 changes also across the population. According to the Observa study, women are more inclined to quarantine than men, as are people over 60 and people with lower educational qualifications. The tendency to underestimate the problem is more common among young people (15-29 years old) and adults (30-44 years old). Among the latter, one in three consider the coronavirus concern to be excessive, while one in five young people consider the virus slightly more dangerous than normal flu. Regarding geographical differences, public support for quarantine is more widespread in the Northwest, whilst the tendency to underestimate the risk of the disease is common in the South and the islands. It is striking that in the North-East, already hard hit by the pandemic, more than 18% of respondents consider COVID-19 slightly more dangerous than normal flu.

Studies of memory and anchoring to worldview knowledge show that it is difficult to correct misinformation once it has been believed by somebody. It is also difficult to stop the spread of misinformation because there is currently no Public Service patrolling and clearing the internet from false information and the sheer amount of information being transmitted per second makes this an enormous task. As with stopping the contagion, basic digital sanitary practices can help us stop misinformation. First by relying on information coming from trustful sources, look for official data; be critical and look for facts when one reads and think twice before forwarding a message, a video or an audio one does not know the credibility of the source.