Facebook testimony highlighted the mental health dangers, but research suggests it matters plenty how you present scientific data on a contentious issue like this.

By Sara Degli Esposti, CSIC

Are social media bad for your mental health?

That’s a question that dominated news headlines this week following explosive Congressional testimony by a former Facebook manager that the world’s biggest social media company commissioned and covered up research showing its products are harmful – especially to impressionable teenagers. Facebook tried to discredit the testimony; but as a group studying online misinformation, we know that this is a long-running, and much-disputed, area of social science.

For instance, in a 2018 book ‘Ten arguments for deleting your social media accounts right now’, Jaron Lanier, an American tech visionary best known for his early work developing virtual reality, argues that social media are making people angrier, more fearful, less empathetic, more isolated and more tribal. Thus, he comes to the conclusion that deleting social media is highly advisable. Is it true? Are social media, which are supposed to bring us together, tearing us apart?

Well before the dramatic Washington testimony, several published studies showed a small negative relationship between the use of social media and young peoples’ mental wellbeing – but this effect has been debated. For instance, in Nature magazine in February 2020, Jonathan Haidt of New York University cited evidence of a correlation between rising social media usage, and rising mental health problems among teens. But another researcher in the publication argued that there could also be positive effects. And separately, Cambridge University’s Amy Orben has argued that a lot of the research in this field is “low quality” and a more rigorous scientific approach is needed. Thus, scientists are (as usual) divided.

So what do most people – citizens, rather than scientists – think about it?

To find out, last year we asked 7,120 people across seven European Union countries: France, Germany, Italy, Spain, Poland, Hungary and the Netherlands. The result was unambiguous. Most people agree social media are harmful. But the story is more complicated than it might at first seem.

We presented the respondents – diverse in age, gender and socioeconomic status – with a statement that “several studies show” a correlation between screen time and poor mental health. In all, 83% of respondents said they agreed there is a problem, and 57% said they would consider deleting some of their social media accounts.

But then we offered them the chance to check out the assertion for themselves – in short, to make a more informed opinion. Surprisingly, given how cynical politicians can be about citizen engagement, 77% said they would indeed like to check the claim further. Among those who did so (we made it fast and easy for them), 86% said they’d like to know even more about the effects of social media. And after checking, the share of people who wanted to delete their social media accounts actually rose by 5 percentage points, to 62%. In short, with more information, the social media problem now appeared to them to be even worse than they had first thought.

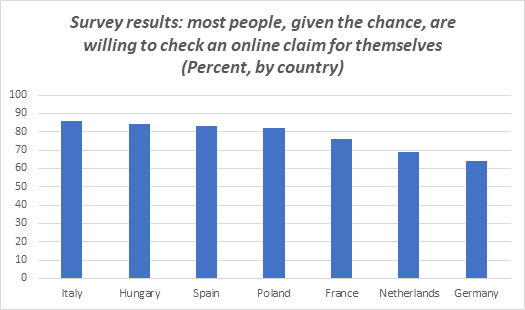

So it matters how you present this kind of contentious social science data to people. But more important, it shows many people are willing, if given the chance, to look at the facts for themselves. Interestingly, there were some pretty clear national differences in this show-me attitude. Italians were the most likely to want to see the data for themselves. Germans were the least interested, but also those who trusted institutions the most. Why the difference? History, culture, media, politics – there are all kinds of factors differing from one country to the next that affect how people view contentious data.

Our research into social media and misinformation is continuing, and we will be reporting more findings from our surveys and other activities. The work is part of the TRESCA Horizon 2020 project coordinated by Erasmus University. In fact, we are developing an app, Ms.W. (the Misinformation Widget) to help people check for themselves the veracity of claims about science that they see online. It responds to a well-document problem of “cloaked science”: false claims dressed up to look like science. In the pandemic, we have all seen how damaging this can be if unchecked: thousands of people have unnecessarily died because they believed false claims about vaccines, treatments, masks or social distancing.

A widget like this won’t solve the problem of social media and teenage mental health. But it can slowly contribute to getting more people to realise they shouldn’t believe everything they read about science in social media.